It is a topic that never ceases to inspire filmmakers or intrigue psychologists. A topic that has been well chronicled in books and films. And quite frankly, a topic that should never be set off the table. But for those whose lives it has shredded, this remains a particularly painful subject to be seen repeatedly on the screens. But here’s where the silver lining lies. In the audience, there are many who identify with the protagonists of such stories and have suffered silently. Their humiliation, fear, angst needs a vent. That is where Marcellus Cox’s 19-minute short comes into play.

The story of Mickey Hardaway, a sensitive, polite and uber-talented artist, on the cusp of his career is marked by only one single theme in his life, that of abuse. The word itself is so strong that it does not take long to conjure up images in one’s mind. And Cox does it intelligently and subtly, depicting the horrors of almost every kind of abuse. Not everything is shown, but what is, is denotative.

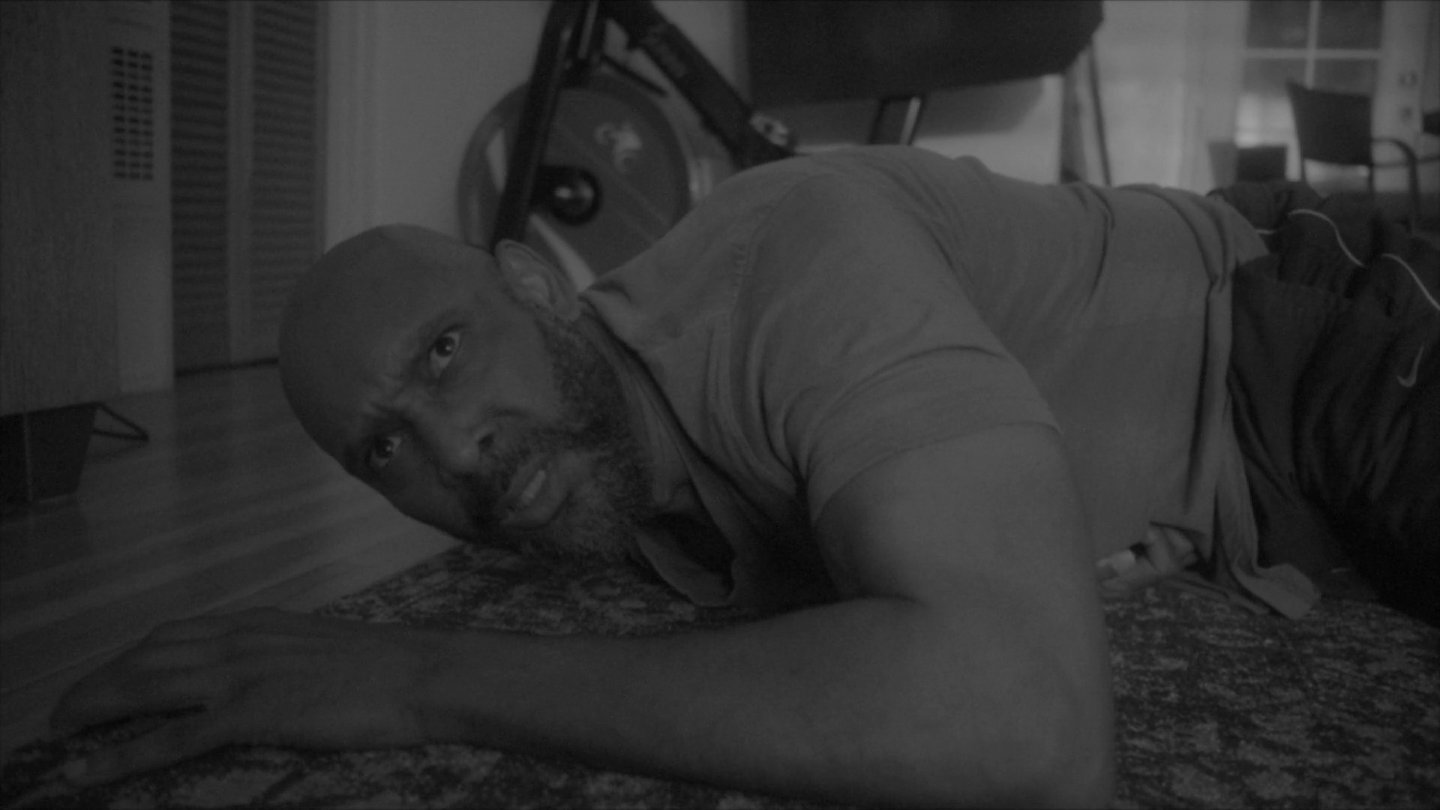

Mickey Hardaway (Rashad Hunter), who is on a call with mentor Mr Pitt (Charlz Williams), quickly realises his future is at stake. The University application has not reached him and we (as well as him) can guess the reason for it. We get enough hints of what Mickey’s life is, simply by looking at Hunter’s portrayal of him. Be it his cautious gaze or the cowered gait in his walk, this is a person who has retreated into his safe world, of his sketches and isolation. That the setting of the film, particularly scenes of him against wide, desolate public spaces adds to the storytelling (he is lonesome and prefers to stay that way) is impressive. His talent, that we realise through the artwork (by Jonte Drew) carefully placed beside him, does his imagination and skills more justice than his words ever will. This is where Cox’s genius in filmmaking shines—in the subtlety. There are no grand intellectual discussions or heaps of praises bestowed upon him. But just the mere, silent display of his work that lets the world know of this budding artist. He is not eloquent with his words, he does not openly invite anyone in, but in the choice of the monochromatic colour scheme, the viewer gets the message-this is Mickey’s world, devoid of all life (and colour).

It is in the simple, pragmatic choices made that Mickey Hardaway becomes effective. The opening scene involving the conversation between him and his mentor, to the subsequent violent attack faced, that we begin to breathe in the same space as him, and it is frighteningly real. Hunter embodies his character well. The shy, frail reserve suits him and does not come across as unnatural. As if the brutality of the outside world (scenes with Patrick played expertly by DeAngelo Davis are particularly unnerving) alone was not indicative enough, Cox takes us along to his inner world, and here domestic abuse comes to mean something more: humiliation.

It should not come as a surprise to know that most cases of abuse that go unreported are the ones that happen on the domestic front. By smartly pitting the father and son in the same room, Cox effectively highlights this issue, while also laying the groundwork for Mickey’s family, the generations of abuse endured silently, that is passed on from father to son, as a prized heirloom. The father, Randall Hardaway (David Chattam), whose quick to rise temper meets its ally in the booze is furious when a bruised and battered Mickey arrives home. It does not cause celebration over an unopened University letter or draw horrified concern from the father, for his son’s bandaged face, but makes for yet another abuser to vent his ire. When after all this, the story takes us to Mickey’s psychiatrist Dr Harden (Stephen Cofield Jr), it is here that we get the answers, the analogies and the painful truth carefully hidden in plain sight. Society makes abuse acceptable, nurtures it, like the mother cradling her child. It is grown, nourished and eventually seeks to fill its appetite. The unwitting suspects, victims of it end up questioning, suffering for the rest of their lives simply trying to feed it.

As macabre as the home front gets, cinematographer-colorist-editor Jamil Gooding’s exceptional work at maintaining the pace of the film (or its colour palette) only brings to respite the breathable ambience of the counselling sessions at the psychiatrist’s clinic. Bob Bradley, whose music hits its full note only towards the end, makes it doubly impactful when neither Mickey nor the audience is granted their closure.

As in most cases of abuse and subsequent trauma, healing is never a one session phenomenon and Cox makes it abundantly clear. The actors are credible and bring forth a believable portrayal of abuse and abusers, and each with their own shade adds colours to the monster that finally devours its victim. Through their accurate depiction, what the ensemble manage to achieve is make Mickey a breathable, living character, for whom we ache, rendering the climax only that much more impactful.

#ShortFilmReview: Mickey Hardaway: Does every parent deserve a child? Share on XWatch Mickey Hardaway Short Film Trailer

Mickey Hardaway: A Slow Drama On The Many Variations Of Abuse

-

Direction

-

Cinematography

-

Screenplay

-

Editing

-

Music