Filmmaker Jevan Chowdhury embarked on an ambitious journey to create 12 films in 12 months, a project that not only tested his creative limits but also proved to be a transformative experience. From his diverse background in architecture and graphic design to his extensive work in commercial and branded content, Jevan’s journey into narrative drama is a testament to his entrepreneurial spirit and unwavering dedication to storytelling. In this interview, he shares the highs and lows of this monumental challenge, offering insights into the creative process, the importance of collaboration, and the lessons learned along the way.

Indie Shorts Mag: You took on the ambitious challenge of creating 12 films in 12 months. What inspired you to embark on this project, and how did it push you creatively and professionally?

Jevan Chowdhury: The inspiration behind this project was sparked by a mix of people, books, and moments that pushed me to say yes. But to keep it simple, I’ll focus on the three drivers that pushed it from idea to reality.

First. I wanted to transition from commercial work to fiction. The problem was I didn’t have any work to show that I could actually do it. While writing an application for a master’s in Directing Fiction, I assumed my 20+ years making commercials and dance film work would provide plenty of material. However, when I reviewed my portfolio, I saw none of it counted. I needed to fix this. I needed to prove to myself at the very least that I could make fiction.

Secondly, I needed to develop my writing. For most of my career, I had focused on idea-led, image-led, movement-led, and sound-led storytelling, creating work that relied heavily on visuals to communicate. I’d written scripts for commercials, but they lacked the grammar of storytelling—the structure, the beats, the emotional arcs. This project was an opportunity to think differently and grow.

Finally, I needed a framework to achieve all of this. 12 Films in 12 Months felt unforgiving and challenging, but above all, it was clear. There’s no escaping the simplicity: one film, one month, repeat. To reignite my work in devising, writing, and collaborating with actors—all while maintaining ‘business as usual’—I needed an uncompromising, foolproof goal. This project delivered that.

I had many concerns.

How would I afford it? Would it actually be beneficial, or would I just become really good at making zero-budget films? Who would help me? What about heart attacks? And, worst of all, would these films even be any good?

I stopped catastrophising. I needed to start somewhere and this was my starting point. I knew the work might be shit. But I also knew I had to make some shit, learn from it, and move on. I’d done the reading, taken the short courses, and talked enough. Now, it was time to do.

You ask how this pushed me?

Having trained as a designer, editor and cameraman I knew a bit about filmmaking. I had tackled impossible projects before. The difference here was money. I didn’t have any. No funding. No grant. No sponsor. I hadn’t applied for any and any knew that this process would stifle me, well, at least on this particular challenge.

That was tough.

But, even harder, I was forced to think about story first and images last—not relying on soundtracks or cinematography, but text.

For the first time, I prioritised the script. It made me spend a disproportionate amount of time on writing, particularly on endings.

To be honest, I thought I would be find scripts and adapt them. This was not the case. I had to start from scratch every month.

Professionally, it was of course good for resourcefulness and adaptability, but by far the hardest push was to become a writer and storyteller.

Indie Shorts Mag: Can you walk us through your process of producing a new film each month? How did you manage the logistics, from ideation to post-production, within such tight deadlines?

Jevan Chowdhury: I realised early that achieving this project would be impossible without a client—someone to provide feedback and accountability.

In November 2023, before I started, I found the courage to email Col Spector, an incredible NFTS tutor I’d met on a short course. I asked if he’d be my accountability partner.

Col’s work is phenomenal and his brutally honest feedback was exactly what I needed. He said yes.

That positive response gave me the confidence to seek a second mentorship and guide – Jerry Rothwell, a friend and remarkable feature documentary director I’d known for years. Jerry knew me and so brought a different perspective, regularly meeting with me to offer invaluable feedback.

Both Col and Jerry pushed me in different ways. I needed all the help I could get.

But mentors don’t make the films. That was on me.

I desperately wanted a producer to join me on the journey, someone who could share the load. But in real life—unlike film school—everyone needs to be paid—all my contacts were in the commercial world and this means I had ADs, PDs, and industry friends who chipped in when they were available. But, to be honest, the bulk of the work landed on my shoulders.

I’ll do my best to explain.

On day one of each month, you’re alone in a room and you need an idea—something compelling, practical, and achievable. What will the film be about? Where will it be set? The number of possibilities is daunting. You can do anything—but can you? The hardest part is making decisions between what I want and what realistically I can create.

Day one is critical. The idea shapes everything.

Forget boats and helicopters; think local—a car park, a field, a house. Think affordable. But it also has to inspire, not just you but everyone involved.

You’re constantly criss crossing fantasy with reality. It’s torment. Lots of great ideas are closed to simply because you don’t have the means.

By day two, you need to sum up your story in one sentence.

By day three – writing.

By the end of the week, you really should have 5 pages of script with characters, plot, directions – clear, realistic and compelling enough to rally your cast and crew.

Is it good? Is it affordable? Is it doable in the time? It has to meet all three criteria.

I often spent longer on the script than I intended—sometimes deep into week two—because without a solid, structured three-act script, I couldn’t move forward. While I knew the casting would help refine the plot and characters, I needed the bones of the story in place to stay true to my core goal: developing my fiction-writing.

With no time for rehearsals, self tapes were a god send. I can’t quite explain how much respect I have for actors.

Once the script was ready, the chaos began: finding the right actors, locations, props, wardrobe, creating schedules, shot lists, meals, risk assessments, and, of course, coffee. All this while juggling a day job, family commitments, and life.

I was reminded regularly to Keep It Simple Stupid.

By week three, I would have shot something—somehow. Week 3 shoot wraps were crucial to leave Week 4 for post-production. It was gruelling.

I scheduled regular meetings with Col and Jerry on the 28th of each month to keep myself accountable.

Knowing someone was waiting to see the work drove me through the late nights.

This process wasn’t smooth, and it wasn’t easy, but it was necessary.

Indie Shorts Mag: What were some of the biggest challenges you faced during the “12 Films 12 Months” project, and how did you overcome them?

Jevan Chowdhury: The biggest challenge was coming up with a script that would excite me every single month.

I was the primary pressure point in this project. I was pushing myself. The logistical challenges—freezing hands, continuous rain, feeding everyone, etc—were all expected. But the isolation of doing all the writing was tough.

I relied on writer friends, non writer friends and strangers. The weight of creating, organising, and delivering the films month after month fell squarely on me.

Without a regular team to bounce ideas off, the process felt isolating. And so with only a few consistent crew members, I became good at building relationships and new teams.

For every project, I ensured I would work with new people and engender the same excitement and energy I felt at the first. I generated a new momentum every month. A much needed force to keep me going across 12 months.

Ironically, one of the reasons I undertook this project was to escape the constraints of client funding and the compromises that come with it. This freedom was exhilarating but also its own kind of burden. Without external accountability or a budget, I had to make tough decisions about what was achievable versus what I wanted to create. Balancing creative ambition with reality was an uncomfortable and ugly ongoing battle.

My kit was stolen in month three. Someone walked into my studio at lunchtime and waked out with my edit suite and my colleagues lenses. This was unexpected and not a nice event to deal with.

Securing the cast and crew was a relentless challenge. I often devised scripts in languages I didn’t understand—and moved into editing knowing that I’d need to subtitle hours of rushes. That was tough, but was a requirement to keep me interested and to keep the project interesting for others.

By the end of each month, I’d feel euphoric for about an hour, knowing I’d finished a film, only for the dread to set in as the process began again.

Professionally, I’ve managed commercial projects with absurd constraints, but this was the most challenging thing I’ve ever done. It forced me to strip everything back and focus on storytelling first. I couldn’t rely on beautiful cinematography or soundtracks to carry the work. I had to write, rewrite, and rewrite again—especially endings, which were a recurring weakness.

Creatively, the relentlessness of the project forced me to adapt. Every month was a lesson in prioritising and simplifying.

There was no magic AI software to write my scripts. If anything this was a massive distraction. There was no magic forum to find free crew and free actors to help out. If you want to do things properly you can’t take shortcuts.

Success wasn’t guaranteed. I questioned my sanity, doubted myself constantly, and wanted to quit many times.

But the driving principle was simple: I had to finish.

That relentless focus shaped everything. I spent most of 2024 eating whilst standing up.

It felt like a blur and I’m not sure how to describe the challenge other than to compare it to British weather – lots of storm, with little calm.

This project wasn’t just about making 12 films. It was about proving to myself that I could make fiction and use storytelling in my own way as an art form. It was a gamble, but one I’m glad I took.

I couldn’t have done it without the invaluable support of the people who stepped in along the way. Their contributions made all the difference, and I feel incredibly lucky to have had them on this journey.

Indie Shorts Mag: Did working on a monthly film schedule influence your storytelling approach or the themes you chose to explore?

Jevan Chowdhury: Before starting this project, I had a list of story ideas I wanted to make — one about shadows, one about radio listeners, one about religion. But when faced with the reality of producing an actual story each month, I realised ideas are cheap.

Many of those ideas were just that – ideas. They were scenes, not fully formed stories.

A story is something completely different. It is a journey in which one person, someone you understand as a character, undergoes a transformative experience, something that changes them for life, either positively or negatively.

Something happens to someone. Thats what a story is.

It has a clear beginning, middle and end and it must not be entirely predictable.

So all my pre-cooked ideas were dead. None of them were doable within a month and none of them were stories!

I needed actual stories that were doable, grounded, and possible to execute within the constraints of time, budget, and resources.

The last thing I needed was cerebral works of art. Been there, done that. See my Moving Cities project, https://moving-cities.com as an example.

For this project, I needed concrete stories that could be understood on the page first.

As you might have noted, the characters I envisioned weren’t always English. They seemed to belong to other languages and cultures. This became one of the most fascinating aspects of the project—I followed this thread because it simply intrigued me—translating my personal experiences into another cultural context became part of the series exploration. It forced me to think about how universal themes and emotions could play out in a different cultural lens.

Watching these films now, I’m struck by how much more they rely on behaviour, performance, and subtext rather than dialogue.

At times, it felt like I was avoiding English entirely, though I’m not sure if that was intentional or instinctive. I became fascinated by actors who could speak multiple languages. I would sometimes adapt stories entirely for them.

I’m not sure if my dance/movement film background or my international heritage inspired this series genre, but either way, I ended up making many of the 12 films in different languages I didn’t understand.

There’s something liberating about storytelling in a language you don’t fully understand—it shifts the focus to the visual and emotional elements.

I’m sure this aligns with my background in magical realism filmmaking. Suppressing that instinct was difficult at times, but perhaps the foreign-language element became a way to explore it indirectly.

Practicality also heavily influenced my themes.

Every idea had to pass a “doability” test: Could it be made within the time? Did I have access to the locations? Could I find the right actors? I’ve worked extensively with child actors in the past, but I knew how difficult licensing and logistics could be, so I only included them when absolutely necessary!

Indie Shorts Mag: Among the 12 films, is there one that stands out to you personally? What makes it particularly significant in your journey as a filmmaker?

Jevan Chowdhury: All 12 films were special, largely because of the incredible people I worked with. But the ones that stand out most are those that provoke a strong physical response—whether it was pouring my heart into a script that left me in tears or witnessing an actor bring something extraordinary to a scene I hadn’t anticipated.

Casting was a crucial part of the process, and I spent more time on it than I probably should have. I was deliberate about finding actors who not only had the skills but also the interest in collaborating.

That said, at least half the films featured non-actors due to budget constraints. In those cases, I relied on people I knew or cast individuals looking for acting experience, often spending lots of time identifying those who might have natural talent or presence.

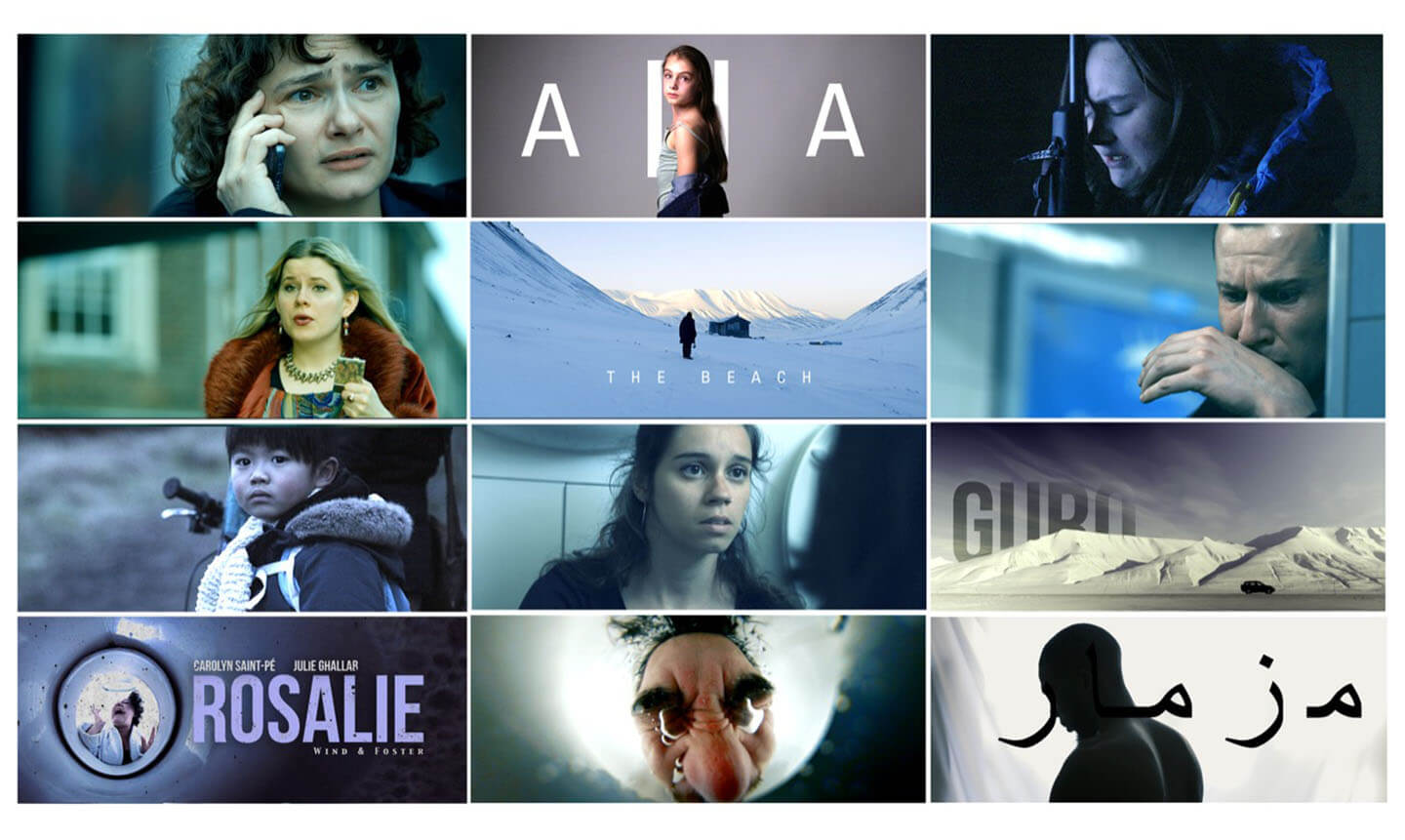

The films I shot in the Svalbard hold a special place for me because of the physical and logistical challenges, but also the emotional depth they achieved.

Ideally I would have shot each short in a different city.

‘Rosalie’ stands out because it was a film made to a brief. In June, I asked one my mentor, Col, to provide me with a brief so I could focus purely on writing the script instead of being responsible for the concept as well. He plucked a tabloid article about a woman who took magic mushrooms. I hated the concept, but at least I had a starting point—and sometimes, that’s all you need.

‘Sylvia’ remains memorable for the extraordinary cast. I loved working in Polish and in fact this film had three languages in it, in large part because that’s the cast I found.

What makes these films significant is the understanding I gained of my ability to cast and collaborate with actors. While I’ve always had strong people skills—this process proved I could successfully translate those skills into drama.

Indie Shorts Mag: You’ve mentioned that to succeed in filmmaking, one must be entrepreneurial. How did this mindset contribute to the execution and success of the “12 Films 12 Months” project?

Jevan Chowdhury: I don’t think it’s possible to make films on this scale and in this genre without being entrepreneurial.

About 15 years ago, while working at the Central School of Speech & Drama as a filmmaker documenting events, I was struck by one of the tutors, Karl Rouse, who championed the idea of the ‘the entrepreneurial artist’. He believed that, contrary to the traditional view, whether you’re a ballerina, actor, or filmmaker, you need entrepreneurial skills to navigate today’s creative industries.

I don’t know if this is entirely true, but it’s a perspective that’s stuck with me. For me, the reality of making a living in filmmaking has demanded entrepreneurial skills.

I’ve had to learn to push projects forward, find resources, and solve problems creatively, because if you don’t make it happen yourself, it won’t.

The ’12 Films in 12 Months’ project would have been impossible without this mindset. It wasn’t just about creativity; it was about resourcefulness, and persistence. I had to pitch ideas, secure actors and locations, and manage budgets, schedules, and deadlines—all while working within tight constraints.

These are not necessarily the skills of a writer/director are they?

There’s something to be said for the classic approach of mastering a single discipline, but for me, being entrepreneurial has been essential to survival.

Ultimately, the project reinforced that filmmaking, especially at this level, requires more than just creative vision. It the willingness to build something from scratch with no guarantees.

Indie Shorts Mag: How has your diverse background—from architecture and graphic design to motion graphics and commercial work—shaped the films you created during this year-long endeavor?

Jevan Chowdhury: Everything I’ve ever done can be equated to problem-solving.

Studying architecture taught me to design within creative constraints; to consider physical space, culture, functionality, and cost.

Similarly, graphic design and photography taught me to distill an idea to its essence, whether in a single image or identity.

This discipline in refining and executing concepts has been important in shaping the stories I tell.

What’s new for me in this project is translating a conceptual idea into a narrative. While I’ve written countless campaigns, storytelling as a structured, psychological craft is an entirely different discipline – its pure writing, which is new to me in many ways.

My experience working with commercial clients brought an ability to work under intense pressure and a focus on engagement and especially, to value the audience.

I do have something to say and ensuring my work resonates with the audience who I care about simply means finding the right balance between connection and authorship.

If it doesn’t interest me, I know it won’t interest anyone else. I think using yourself as a barometer is primarily a good thing, but everyone is different and you must always be open to new angles.

Indie Shorts Mag: The project seems to be a pivotal move towards your goal of transitioning into narrative drama. How have these films prepared you for this next chapter in your career?

Jevan Chowdhury: I’ve spent most of my career navigating a world where projects often start with resources, clear objectives and a team to bring it all to life. But stepping into 12 films in 12 months has been the opposite—there are no guarantees, no budgets, and often no collaborators unless you create something compelling enough to attract them.

That’s what 12 Films in 12 Months was about: building something from scratch, testing my ability to tell stories that matter, and showing potential collaborators and backers what I’m capable of.

I know that the industry isn’t built to make it easy for someone transitioning from commercials to drama. It’s crowded, unpredictable and tough to break into. But what I’ve learned is that being entrepreneurial isn’t just about making things happen—it’s about making them happen sustainably. I don’t just want to create stories; I want to create a foundation for the next chapter of my career, one that brings collaborators and resources into the process.

In short, I hope this project is the starting point for a bigger journey, one that grows not just with the stories I tell, but with the people I tell them with.

Indie Shorts Mag: Collaboration is key in filmmaking. How did you handle assembling and working with different teams for each of the 12 films?

Jevan Chowdhury: Collaboration was at the heart of every film I made during this project, but so was identifying the right people to collaborate with. From scripts to shoot to post, I sought input from friends, actors, and mentors, even sharing early drafts for feedback.

I quickly realised that one good collaborator is worth their weight in gold.

On shoot days, I learned that assembling the right team wasn’t just about technical skill—it was about finding people who were genuinely interested in the project. With limited resources, I had to ensure everyone involved shared the same energy.

Casting was particularly critical. I often welcomed actors help to refine characters and develop scenes. The chemistry between actors and crew could make or break a shoot, and I spent more time casting than perhaps I should have—but it always paid off.

One of the biggest lessons I learned was the importance of listening.

Whether it was an actor concerned about their lines (or lack of them), a crew member raising practical obstacles, or a mentor offering critique, being a good listener became essential.

This openness allowed me to adapt when necessary and ensure the team was moving forward.

I worked hard to understand feedback. Seeing things from others’ points of view is invaluable, and if anything, it’s impossible to see the whole picture without these angles.

Collaboration is a personal thing that you have to work hard at to make it work. It’s a balance of communication, attention, and mutual respect. It’s about how you talk to people, how you observe and respond.

This might seem basic, but trust really is the key!

Indie Shorts Mag: Now that you’ve completed the “12 Films 12 Months” challenge, what are your future plans? How do you envision building on this experience to further your passion for narrative drama?

Jevan Chowdhury: Right now, I’m continuing to work on documentary projects for clients mostly focussed on climate science, sustainability and global issues surrounding inequality.

While I’m passionate about these themes, I’m determined not to lose momentum in my journey into drama.

The first step is hosting an industry screening for the 12 Films project. This isn’t just a celebration—it’s a platform to showcase the work, spark conversations, and connect with people who resonate with these kinds of stories.

I’ve seen other filmmakers take on similar challenges, and I know how much sacrifice it requires—not just financially but creatively and emotionally. It’s important to me and for all involved that these films find an audience, and I’m encouraged by the fact that some of the work has already been invited to festivals and picked up for representation by Festival Formula and The Festival Doctor. It’s early days, but I’m optimistic about the films’ potential festival life.

Beyond that, I’m revisiting a script I’ve been developing for a couple of years. It’s an idea I’ve wrestled with, but having crafted 12 structured stories this past year, I now feel more confident in my ability to bring it to life.

My focus will be on scripting it thoroughly before moving into production. However, I recognise the importance of accountability—whether through funding, a producer, or a client—to make it happen.

I’ll also be actively seeking producers and development partners to pitch ideas and create projects with, as well as exploring commissioning and investment opportunities.

Ultimately, I’m looking to work more in the drama film and TV space, collaborating with like-minded people and continuing to refine my craft as a storyteller. This project was a significant step and I’m excited about what comes next.

Jevan Chowdhury’s “12 Films 12 Months” project is a testament to his unwavering dedication and entrepreneurial spirit. As he continues to transition into narrative drama, the lessons and experiences from this endeavor will undoubtedly shape his future work. For filmmakers and viewers alike, Jevan’s journey serves as an inspiration, showing that with determination and a clear vision, even the most ambitious goals are within reach.